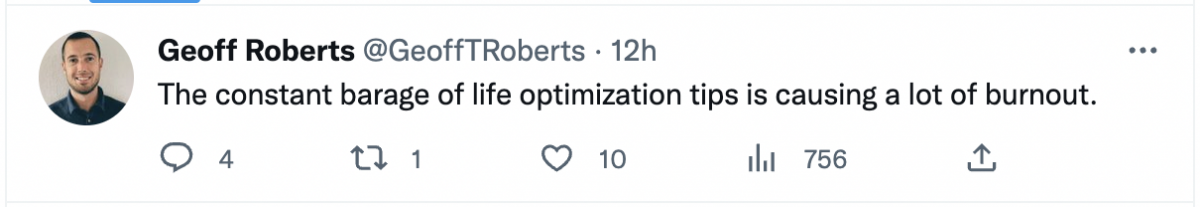

Yesterday I posted this tweet, and almost immediately my direct messages lit up.

It's clear that a lot of people feel this way, so I figured today is a good day to share that I've signed a book deal. My book is forthcoming this spring, and is entitled:

Paralyzed by Process

How the endless barrage of goal setting frameworks, process improvements, and life optimizations are making an entire generation miserable

The forward is written by Sahil Bloom, authored from the confines of his padded room in a mental hospital in upstate New York. After his 82 daily processes started conflicting with each other, the CPU that is his brain short-circuited, unsure of what process to execute on next. I'm happy to report that he's OK.

(I'm just picking on Sahil because he's well known to most people reading this and something of a poster boy for process improvements. He's super successful, I suspect he has a thick skin, and he writes lots of great stuff—I particularly enjoyed this. He'll be fine!)

All kidding aside, I think this is an important topic worthy of further exploration.

The self help genre is implicitly good

I want to start by saying that I genuinely believe that the vast majority of people who publish self help, or lifestyle design, or goal setting related content have inherently good intentions. They are trying to help other people, and there's a massive appetite for content that helps us lead better lives. That's a good thing any way you cut it!

But the appetite for such content is so severe—and there's so much financial opportunity here—that our feeds and ears are overflowing with this stuff. It's almost impossible to get away from it, even with deliberate effort.

Whether you're consciously consuming this stuff or not, on a subconscious level it's tough to deny that it has an effect on us—it leaves us wondering if there's more that we can be doing, more that we should be doing. It's creating a bit of a rat race, both internally and as we compare ourselves to other people who may just be executing on that game-changing framework. Are we getting left behind?

The prevalence of this content has leaked into all areas of our lives—it's not just focused on how we run our businesses, or plan our mornings, or optimize our time.

Did you know that if you brush your teeth for 5 minutes, twice per day, and start with 30 counter-clockwise circular brushing movements on your bicuspids that you reduce you chance of cavities by 13%? Over the course of your lifetime that will save the average American $4,982...

Can you afford not to take brushing seriously?

My overarching point in writing this post is simple...

"At some point life is meant to be lived rather than optimized."

I want to share a bit of my own evolution on this topic to support my point.

My experience stepping away from process

As we discuss this topic, the appropriate disclaimer is that everyone is different. Some people need process—it helps them thrive. For others, process is a pin in their balloon.

And that's OK!

As for me, I've never been a particularly "Type A" person. I'm not naturally terribly regimented and I wouldn't describe myself as a process lover—but I'm a huge believer is setting yourself up for success.

I do go out of my way to create environments that I believe are conducive to helping me achieve whatever it is I'm hoping to do. I actively look for ways to create win-win scenarios. And throughout the vast majority of my life, I'd say I imposed a good deal of regiment and process on myself despite it not coming naturally to me. I did that through work ethic and will, largely because I viewed it as a prerequisite for success.

Over the last 5 or 6 years, I've increasingly taken steps away from this. I don't follow a goal setting framework and I don't overly regiment my days. I've tried to instead lead a much more organic life, where things unfold more... naturally. And what I've noticed is that not only is this freeing, but it's actually led to improved performance and happiness in many areas.

I'll give you two examples—one from my business, and one from my personal life.

When it comes to my business, I'm constantly bombarded with feature requests from our customers—improvements that they suggest we make to our software. This sort of challenge makes process improvement gurus salivate—they've got all kinds of grids and Venn diagrams that I need to use to assess the level of effort versus the reward for building any of the features that are suggested to me.

You know what I've opted for instead? Nothing.

Sure, we have a backlog where we jot down feature requests. But in terms of prioritization frameworks, I've got nothing in play. What I rely on is simple and organic—I spend all day every day talking to our customers. The ideas that keep coming up consistently over a long period of time are the good ones—those are the ones that we prioritize. Good ideas consistently make a case for themselves.

Beyond that, we long ago discarded the notion of goal setting at Outseta. It's been one of the more freeing decisions I've made in my career, and I'm confident it's made us more successful.

In my personal life, I have twin 3 year old boys. Anyone that's raised a child will tell you that routine and structure is important—it is. But I see so many parents become completely obsessive over every single aspect of how they raise their kids. There's a plan for how they'll be fed, how they'll go to sleep, how they'll learn to tie their shoes, and even how they'll play.

While that's proven useful in some instances, it's also caused misery in others. It's not that I don't want to read 12 different parenting books, each sharing their own proven methodologies (OK, maybe that's part of it...). It's that I can't help but reflect on all the children that have been raised in the history of humanity—the vast majority ended up OK, without any of this overbearing nonsense. To say that we need this stuff is to deny thousands of years of evolutionary history.

So when in doubt, I've opted to embrace the challenges of parenting as they come. Without question, that's brought some degree of sanity back to my life a parent.

Consistency and habits

While I'm seemingly bashing frameworks, process, and goal setting—at least a bit—I'm the first to advocate for the importance of consistency and habits. These are not one and the same.

James Clear is the author of Atomic Habits, a well known book whose primary premise is that the habits you create are essentially votes for the type of person that you are. Whether you like it or not, your habits become part of your identity.

I believe this to be true!

In my personal life, I've developed the habit of working out 5-6 days per week for 45 minutes since I turned 30. Because I've done it with such consistency it's almost automatic for me now—and it's become in many ways a part of my identity. I'm proud of this habit!

In my work life, I've woken up every day for over 6 years now and focused and making Outseta incrementally better. Again this has become a part of me and is something I'm proud of. But it terms of what my workouts or workdays look like, there's very little that's regimented—there's very little process.

Let me put this very bluntly, because I think it's important.

"While I'm not particularly good at following regimented processes, I'm quite good at doing things with consistency over a long period of time. And I think the latter is far more important that the former."

It's likely at this point where you're having the obvious thought...

"Yes you idiot, but for a lot of people a process is required to develop consistent habits."

That's absolutely true—I'm not here to argue that. But once you develop a habit I do think that overly regimented processes often impede us from doing our best work.

The role of reps versus inspiration

All of this comes down to different ways of looking at the world, and of course the most important thing is finding what works best for you. In general I see two different schools of thought, and I'll use writing as an example to illustrate both.

Many people in the business world who create content espouse the benefits of process—they sit down every day, follow the same process, and force themselves to write or create content. David Perrell advocates for this. The general line of thinking is simple—more reps will result in more "hits." You might put out a bunch of stuff that stinks, but by increasing the volume of your output you also put out more good stuff. I don't necessarily think this is wrong—there's a lot of wisdom in it.

That being said, it's hard not to look at this as a major contributing factor to what I see in social media timelines—massive amounts of mediocre content, repurposing the same tired points. It's contributing to the bloat of mediocre ideas and content driven burnout.

The other school of thought is one I've embraced, and writers like Morgan Housel have also espoused. You don't write anything unless you feel particularly inspired to do so—it's inspiration that creates our best work. In this case consistency comes from a commitment to continue writing, over a long period of time, only when you genuinely feel like you can't not write about something.

Personally, I prefer this approach—I think it not only leads to better work, but also declutters our timelines and contributes a lot less to all of the noise that we're bombarded with from all directions.

What you consume is your responsibility

I am not trying to sell you on my way of doing things—I'm only trying to point out that this obsession with goal setting and process and life optimizations sometimes can become counterproductive.

It's your responsibility to figure out what content you consume and what works for you—but the amount of self-help content that we're confronted with today is at the very least... agita.

"Sometimes it takes a process to develop a habit, to develop consistency—but then abandoning the confines of that process is what's actually needed to elevate your performance to the next level."

A great example from my life comes from athletics—in my case baseball, basketball, and golf. Growing up I was obsessed with sports and invested an enormous amount of time in all three of the sports that I've mentioned. I became obsessive when it came to my pitching mechanics and the technical aspects of my golf swing. As I shot free throws I visualized the ball going in the net, bounced the ball three times, and made sure to extend my right arm fully after releasing the ball.

What I found over time was that obsessing over the mechanics and the technical aspects of these sports actually started to hinder my performance. I had already put in the time to learn the fundamentals—continuing to obsess over them became nitpicking that actually made me less likely to perform well. I'd developed consistency in fundamentals and wasn't giving myself the space to lean into my athletic ability—to play unencumbered by technical thoughts.

"I became better at all three sports when I gave myself the freedom to move from being a technical player to a feel based player."

I needed less regiment and more feel. And I think in short, that's what much of this post is about.

I want this post to be a reminder—a reminder than consistency without overbearing process is possible. It may actually be what's required to do your best work.

As the world increasingly latches on to the idea that the freedom to do what you want with your time is the ultimate form of wealth, I want leave you with what I think is an important thought...

Yes, systems and frameworks and processes can actually be used build more freedom, but only to an extent.